Eno Journal

VOLUME 7 SPECIAL ISSUE

Papers from the seminar on Water Wheels and Windmills

JULY 1978

By Jean Anderson

Watermills filled a unique position in rural America before the 20th century. As industrial, commercial, and social centers they touched the lives of people at many points, becoming interwoven not only with the economic fabric of society but with its psychological fabric as well. I should like to discuss these aspects of mills, confining my remarks to the mills of old Orange County, North Carolina.

Mills were first of all industrial units converting raw materials into usable products, most often grain into flour and cornmeal, and logs into lumber. By their owners they were viewed as good investments. Richard Bennehan could report in 1807, a year after he bought his mill on Eno, “My mill now has a handsome run of business.” The initial capital outlay, which varied greatly from mill to mill, could bring a nice return. The Eno River mills cost anywhere from $1000 to $6500. A saw mill rarely exceeded the lower figure. With their usual two runs of stones, grist mills could grind up to six bushels of both corn and wheat an hour. In a ten-hour day this translated into $60 a day for both corn and wheat. Archibald Murphey estimated in 1821 that his Haw River mills yielded a yearly profit of from $1200 to $2000. Census records from 1850 to 1880 give mill statistics and show their productivity. (See Centerfold.) A mill took a toll of anywhere from l/8th to l/12th of what it ground – whatever the market would bear. The mill also took a toll of the miller’s health: respiratory diseases, commonly asthma, were occupational hazards.

Wages for millers were minimal. West Point paid its miller only $150 in 1870; Paul Cameron and John A. Cole paid their millers $200. Before the Civil War competent slaves often ran the mills, thereby saving outlay for wages entirely. Murphey, Bennehan, and Cameron mills were operated this way for years.

Not wages but maintenance reduced mill profits. A mill owner could calculate capital investment, grinding averages, market prices, and wages with accuracy; for other factors – a good mill seat; amount and pressure of water; the size of the wheel, stones, and gearing; and the quality of the stones – he could depend on a good millwright to produce an efficient mechanism; but the factor he could not estimate was repairs.

Photo by Hugh Mangum at the turn of the century.

Mills on Piedmont rivers were exceedingly vulnerable structures. Heavy and continued rain always resulted in freshets that turned placid streams into raging torrents. Even more vulnerable were the mill dams. It was not uncommon for a single freshet to destroy all the dams on a river. When repairs could be made by slaves they were cheaply done; when they required skilled supervision they could be costly. The Cameron family papers,which cover almost two hundred years reveal how frequently their mills were not in operation. Paul Cameron’s sentiments on the subject tell the sad truth; of Cameron’s New Mill he wrote, “Never was a mill sustained and maintained at so much labour and cost in our part of the county.” He characterized the repairs as “at all times to me the most unpleasant and … unprofitable sort of work …” That both his Eno mills lay in the triassic basin may have contributed to their troubles, but his was the common experience of mill owners in this region. Neither Bennehan’s, Cameron’s, nor the West Point mill is listed in the 1850 census, for all were out of order.

Millwrights called in to do repairs charged high prices. Usually they were found in families who passed the skill down from one generation to the next. The Staleys and Dixons were two such families in the area. The 1850 census shows five Dixons listed as millwrights and six other millwrights associated with them in their business. Conrad Staley built Cameron’s Mill on the Flat River in Person County;

Abraham Staley built their New Mill on the Eno. Caleb Dixon was called in to do repairs for them and rendered a bill Paul Cameron never forgot. When he next needed a millwright he wrote his father, “I will keep clear of those free soilers and blood suckers – Dixons!” Mill repairs minimized profits,

As commercial and social centers, mills depended on rather different factors. A frontier settlement could not predict its future demographic and traffic patterns – modern sciences directly related to a mill’s commercial success. The interaction of the growth of settlements and roads is like that of the chicken and the egg: it’s hard to say which came first. And then as now new roads were political matters. A mill needed a location within reach of a burgeoning population of farmers, and roads to bring them to the mill. The location of mills often determined the location of roads and vice versa. Even more than a well-traveled road, a mill owner hoped for a location near a crossroads. Cabe’s mill was on the Fish Dam Rd., a major east-west route, roughly highway #70 today, but Borland’s mill, its closest competitor, in later years found itself not only on the Fish Dam Rd. but on a north-south road as well, running from St. Mary’s Chapel in the north to the New Hope Chapel and further south to Chapel Hill. Borland’s mill outlived Cabe’s by many years.

Well-traveled routes usually incorporated good fords. The wise mill-builder situated his mill beside one. Shoemaker’s Ford was certainly a bonus to the West Point Mill. Even if road patterns could not be predicted, a good ford was always recognizable. Michael Synnott ignored this important factor. There was no crossing at his mill. Neither was there a ford at William Johnston’s mill on Little River. Both mills were out of business before the end of the 18th century.

Even better than a ford was a bridge. Bennehan was fortunate to obtain a bridge at his mill early in the 19th century; the only other bridge across Eno was eighteen miles upstream at Hillsborough. In 1851, thirty years later, the situation was unchanged. In that year the farmers around Dickson’s mill petitioned the court for a bridge there, citing the many days during the year when the river was “past fording”, handicapping the farmers who needed to get their produce to market. They would have got their bridge if pressure from another quarter had not reversed the court order and placed it instead at the West Point Mill crossing, giving that mill an instant advantage over its competitors. Today the site of Dickson’s Mill still has only a ford and lies in a backwater of the county, adjacent to a vast uninhabited area once dotted with homesteads, while West Point Mill stands on a main artery in the pulse of a growing city.

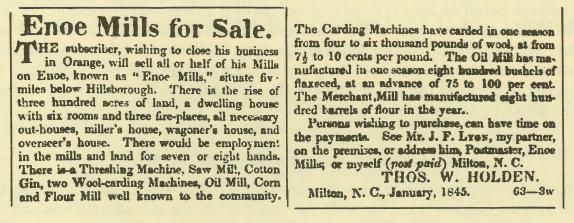

To the people whom the mills served, they meant daily bread; but they could supply other vital services as well. A blacksmith shop was often the first auxiliary service added to a grist and saw mill (many early mills were both saw and grist mills but not all). A smith could make and repair farm and kitchen equipment and shoe horses. Some mills went further and supplied tilt hammers for more sophisticated smithing; McCown’s Mill (later Cole’s) and Dickson’s Mill were tilt hammer mills through part of their long histories. Dickson advertised in 1849 that he made carding machines, wheat fans, wagons, and ploughs. His mill, like many others, had a general store attached to it where he sold flour, wheat, cornmeal, wool rolls, and shingles with a small stock of other food stuffs. Instead of cash he would accept any of the above items and flax seed, beeswax, feathers, and tallow as well. It is plain to see that he had grist, saw, oil, and tilt hammer mills. It is a wonder he did not have a distillery. Whiskey was always a hot item in mill stores, and many mills ran distilleries as part of the mill complex. Dickson did not mention cotton gins or threshing machines either, services offered by his nearest competitor upstream, Lyon’s Mill.

Through all these services a mill strengthened not only its economic base but its position as a community center. It drew to it scores of farmers and their families whose many needs it could supply, and it drew to it the men who performed those services: miller, sawyer, blacksmith, wool-carder, ginner, distiller, thresher, wagoner, and store-keeper and their apprentices and clerks and helpers, all of whom lived either nearby or on the mill tract itself. A symbiosis developed between the mill and the people, between the industry and the society-they sustained each other.

In its social role the mill supplied first a meeting place for chance encounters and for scheduled groups like the Sons of Temperance and other social, religious, or political assemblages. Widely separated on their scattered homesteads, unimaginably isolated, the rural families hungered for contact with other people, a nourishment that the mill freely gave. Against a backdrop of working machines, in themselves fascinating and challenging, the people met. They came to grind their grain and saw their logs, to mend their ploughs and buy their provisions, to shoe their horses and gin their cotton. The sheriff came at appointed times to collect their taxes. The politicians came to make their pitches and exchange promises and whiskey for votes. The federal government made use of the mill, too; the bestowal of a post office was certification of a mill’s centricity and yet another reason to draw people to it. With the post rider and mail came the newspapers and journals and knowledge of life beyond the region.

Men swapped news and views and horses and land. Men came to fish in the mill pond and boys came to swim. At Borland’s Mill bets could be placed on Saturday morning tor races to be run that afternoon at borland s racetrack nearby. At another mill, men held shooting matches. Broadsides tacked to the mill walls told of estate sales, runaway slaves, strayed animals, stud horses, militia musters, quack medicines, and camp meetings, and drew the isolated farm families into the web of a society. The people sensed themselves as part of a group that shared common needs, interests, and experiences; that feeling sustained and supported them.

A Borland descendant proud of his mill heritage philosophizes about the old days of watermills: “It would be difficult,” he says, “to assess the impact of these old mills over the years. I hold with the belief that they had a great and good influence…on the opening up and development of communities.” They gave people a place to meet, to become acquainted, and to exchange ideas on politics, morals, and religion. The mills challenged their owners’ ingenuity to harness nature to perform their needs, to improve and perfect machines, and to convert goods, services, and profits.

These social and psychological functions of mills were certainly not in the minds of their builders, who looked only for financial gain and convenience; nor were they in the minds of the busy farmers who willingly bartered or bought their manifold services. But in retrospect all who lived in the days of watermills acknowledge the wider role that mills played in their lives: the excitement, the pleasure, the stimulation to growth of mind and sociability, and to a sense of identity and membership in a community and in a nation.

Sources

The following sources were used in the preparation of this paper:

The Cameron Papers, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina Library at Chapel Hill.

The Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Censuses of the United States of America, 1850, 1860, and 1870.

The Hillsborough Recorder.

An unpublished article by John Marshall Link, “Information Regarding the ‘Old Borland-McCauley Mill’ and the Community Around the Same.”